Hell-raising tradition

In the last years of his life, Arthur Kasherman roamed about the city of Minneapolis, Minnesota in the constant company of two ghosts, whose names were Howard Guilford and Walter Liggett. The parallels in the three editors’ lives were so striking that Kasherman knew that his obituary, like those of Guilford and Liggett, would be written in blood.

These three angry men are mostly forgotten now, but they were the main characters of one of the most violent chapters in American journalism. In a crowded, grimy and often lawless Midwestern city, the Minneapolis of the Great Depression, they used the printed page to raise hell. They published when they could scrape together the money. They wrote headlines that bellowed outrage, smashing the crooked politicians and cops who were on the payroll of the bootleggers and mobsters who ran gambling houses, brothels and after-hours gin mills. They may have been one-man operations, but in an era when everybody got the news on paper, what was printed and hawked on the streetcorner got a city’s attention.

The mainstream dailies – the Minneapolis Journal, the Daily Star and the mighty Tribune – dismissed these three publishers as scandal-mongers, much the way the corporate media view today’s bloggers. Indeed, the methods of Guilford and Kasherman, who worked together for a time, were sometimes scurrilous and practiced a journalism more mercenary than factual. But Guilford, Liggett and Kasherman were also willing to investigate the powerful and the wealthy in a way that the big Minneapolis dailies refused. They were rewarded with beatings and arrests on trumped-up charges. Police confiscated their newspapers. Their offices were ransacked. More than anything else, they are forever joined in history by the circumstances of their deaths. The equation was simple: get rid of the editor, then the news will stop. On Sept. 6, 1934, Howard Guilford’s head was practically blown off by a shotgun fired through his car window as he drove home. On Dec. 9, 1935, Walter Liggett was felled by machine gun bullets in an alley behind his home, in front of his wife and 9-year-old daughter. Those deaths, for which no one was ever punished, would define Kasherman for the rest of his life.

The most derided of the three, Kasherman was combative, self-righteous, possibly delusional. Behind the closed door of his cheap apartment, his typewriter chattered deep into the night. Kasherman saw himself as a crusader in a fallen city, unafraid of offending dangerous people even after repeated attacks and repression. He brandished his newspaper like a knife. For all his bombast, though, Kasherman was telling the truth about his city.

Arthur Kasherman was born in Russia and immigrated to the United States at age 10. He grew up in the North Side, where Jews were concentrated in segregated Minneapolis, and graduated from North High School. He had a lifelong desire to become a lawyer, like his brother, Edward. But his life kept gravitating toward the far less savory world of newspapers. He was a newsie, hawking papers at 3 in the morning. Early on he showed an enterprising streak. In the early 1920s, he started publishing a seasonal paper called the Newsboys’ Christmas Greeting, and it earned him some decent money. Still, he pursued his dream by attending the Minnesota College of Law. His time as a law student ended in the late 1920s, when he got mixed up in a corruption investigation involving a suspected bribe between a gangster and the chief of police. He was sent to jail for refusing to testify, because, he said, he was a “newspaperman.”

The rest of Kasherman’s life would be a confrontation. His hangout was Minneapolis’s turn-of-the-century City Hall and Courthouse, an immense Romanesque fortress of caramel-colored granite that squats on an entire city block. Kasherman was the lurking character with the hat brim turned down, the collar turned up to hide his face. Under City Hall’s soaring atrium with its opulent stained glass ceiling, the newspaperman sought out the most sordid stories oozing out of the courtrooms, the grand juries and the police interrogation rooms for the “exposes” that were more diatribes than investigations.

His words survive in letters, fragments of interviews and in the columns of his newspaper, and for all their messianic fervor, occasional pettiness and over-the-top rhetoric, they still offer an endearing glimpse of this Runyonesque character. He would call for the elimination of the rodents running the city, alongside an advertisement offering his services as a public relations consultant.

After one setback, friends urged him to go south and become a lawyer. Kasherman refused.

“Those dirty double-crossing rats can’t do this to me,” he spat back. “I want vindication.”

In October, 1936, the well-known proprietor of a downtown brothel approached the Minneapolis police. She complained that Kasherman had threatened to write about the business carried on in her Dobbs Hotel unless she paid him off. She said she gave him $50 in August, another $50 in September. But she wasn’t going to make it a monthly habit. So she invited the police to help her make the third payment.

It’s interesting that the police found Kasherman’s supposed blackmail a greater menace to the public order than a house of prostitution.

The trial in January 1937 was front page news in the Minneapolis Tribune and the Minneapolis Star. Kasherman didn’t disappoint. He leaped out of his chair, yelled at the jury, once even tried to punch a prosecution witness. Alex Kanter, the lead attorney, stood before the jury and even in his defense, hinted that Kasherman’s self-righteousness had the tinge of delusion. He was “imbued with the idea of becoming a reformer — the Huey Long of Minnesota,” Kanter told the jury.

Kanter linked Kasherman with the slain Guilford and Liggett. Putting him in prison was a calculated effort to silence him, Kanter said, although it was “dealing with him more kindly than his predecessors.”

Though it didn’t persuade the jury, Kanter’s closing argument made an impression on the correspondent from the Minneapolis Star.

“His conviction brought speculation as to whether another Minneapolis ‘scandal sheet’ would succeed Kasherman’s ‘Public Press.’ For the third time in recent years the field was left empty, on two previous occasions by the assassinations of Howard Guilford and Walter Liggett.”

Kasherman emerged from prison in September 1940, after serving three years for his $25 extortion conviction. He immediately went back to work, publishing his “Newsgram” and “Public Press,” accusing Mayor Marvin Kline of breaking his promise to “close up” Minneapolis.

On a Saturday night in December 1942, Kasherman walked out of a restaurant on Nicollet Avenue. He went down the street to a drugstore at 16th Street. Before he could get in, two men jumped him from behind. They pounded him with blackjacks and nightsticks as he lay on the ground, until blood was gushing from his head.

When he came to, Kasherman told the cops he had been threatened in recent weeks, and had written letters to Kline and Gov. Harold Stassen complaining about “vice conditions” in Minneapolis.

In the last issue of his newspaper, published in December 1944, Kasherman included a three paragraph “special request” to the county attorney and the sheriff. Make sure nothing happens to me as the result of his criticism of City Hall and its gangster allies, Kasherman wrote. “No slugging, or anything!” “I am sure that both of you officials believe in Freedom of the Press – and that it isn’t necessary to get the underworld’s permission to publish a newspaper. And that it is perfectly proper to expose CORRUPTION in the city!”

Last chow mein

On a slushy night in January 1945, a woman named Pearl Von Wald was stepping out of the Pantages Theater onto the sidewalk when somebody blew the horn at her. It was Art Kasherman, a guy she’d known for years, pulling up to the curb in an Oldsmobile Coach.

Von Wald wore a sharp white overcoat. She also sported a shiner, bestowed upon her the previous night by a drunken gentleman friend. That man, Red Sullivan, had spent a fair part of the day in jail, but Von Wald’s ordeal, worn like a purple badge under her eye, wasn’t going to keep her from going to Hennepin Avenue to take in a movie. Or from getting into a warm car with another male friend to take him up on his offer of some late-night chow mein. Kasherman was 44 years old, and though his wallet was light, he always dressed snappily. The two drove across downtown.

Earlier that day, Kasherman was hanging round City Hall, just like he always did. By one account, he walked into the Hennepin County sheriff’s office with some information about a dice game on Nicollet Avenue that was sending big money to the Chicago mob. Later on, he stopped by the office of the Star Journal. Another edition of the Public Press is coming out, real dynamite this time, he bragged.

“Better watch out, Art,” someone bantered. “Look what happened to Guilford and Liggett.” They said it all the time. He was so identified with those two that the reporters thought it was fun to taunt Kasherman with it.

They can’t scare me, he answered.

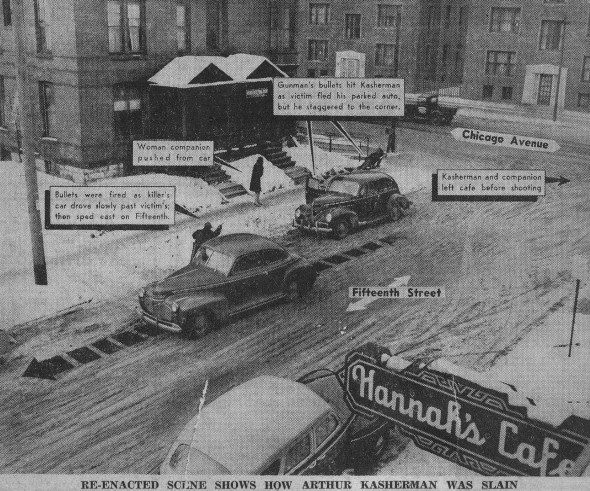

It was 11 p.m. when Kasherman parked the car just across the street from Hannah’s Café at the corner of 15th and Chicago. He and the woman with the white coat and the black eye went inside the restaurant. They took their seats at the second table on the left.

While they were eating their chicken chow mein and drinking steaming cups of tea, things were happening outside, in the darkness. Someone walked up to Kasherman’s parked car. A knife was jammed into left front tire, and the air quickly escaped.

The couple finished up in about 30 minutes. Kasherman walked up to the register and paid the check. He and his date put on their coats and stepped through the double doors into the night. It was about 11:30. Across the street, the organ player at Danny’s Bar was making a racket. Down the block, a newsboy made his way home, his last newspaper sold. The city streets were covered with ice and slush. The couple crossed 15th Street, to Kasherman’s mud-spattered Oldsmobile.

Pearl Von Wald got into the passenger seat. Arthur Kasherman got behind the wheel. He started it up and turned the wheel. The Oldsmobile wouldn’t pull out. Must be stuck in the snow. He tried to rock it back and forth. A man came out of the restaurant and saw Kasherman spinning his wheels. He walked over to the back of the car to help him with a push. Then the guy looked down. Hey, your tire’s flat. Kasherman got out of the car to see for himself.

“I’m sorry, I can’t help you,” said the good Samaritan. Then he got his own car and drove off.

Kasherman got back behind the wheel and closed the door. He turned the key to start it up again, and give it another try, rocking the car back and forth. The windows were all steamed up. They couldn’t see what was happening on the street.

A large dark sedan swerved around the corner from Chicago Avenue and stopped. A man got out and stepped up to Kasherman’s car. In his hand was a .38-caliber pistol.

The driver’s side window exploded. Kasherman screamed as a slug ripped through his cheek and shards of the shattered glass drove deep into his face and neck. He fell over on Von Wald, spots and rivulets of blood painting her white wool coat. She had already crouched down in terror, but the weight of Kasherman pushed her out of the car onto the running board. The shots kept thundering into the car. Kasherman forced his way over her and made one last dash for his life. He ran toward Chicago Avenue, only a few paces away. His head was streaming with blood. The man with the gun followed.

“Don’t shoot, for God’s sake don’t shoot,” Kasherman said. Then he said a name, a short nickname, Bob or Joe, like he knew the person who was killing him. Von Wald heard the name, but she said she didn’t remember exactly what it was.

The pistol roared. A .38-caliber slug pierced the newsman’s chest. Kasherman fell face down on the sidewalk. The killer got back into the passenger’s seat and the big dark sedan sped off down 15th Street with its headlights off, the gunman’s hand out the window, firing two more bullets into the night.

A crowd gathered near the corner of 15th and Chicago to look at the lifeless form on the sidewalk. Somebody who lived nearby at first thought it was just a drunk. There were a lot of those on this corner. Soon the flashbulbs of the Daily Times, the Tribune, the Star-Journal, the Dispatch, the Pioneer would be lighting up the street, and pencils would scratch in notebooks about the gangland-style murder of this curious character. Kasherman’s prophecy was, at last, front page news, all over town.

The aftermath

In the days after Arthur Kasherman’s murder, few would have predicted that it would change the direction of the city.

The killing earned four paragraphs in Time Magazine on Feb. 3, 1945. Its headline properly noted Kasherman was “Victim No. 3,” acknowledging his membership in that sad trio. While imputing some journalistic “legitimacy” to the two previously murdered Minneapolis newspapermen, Kasherman “had none.” It was a “wonder that anyone wasted a bullet on Kasherman,” the unnamed correspondent wrote, deriding his “thin face and slickly pompadoured black hair” and asserting that his newspaper was all about smearing “the cops, the mayor and the gangsters…”

It ends with this disturbing sentence: “Minneapolis’ legitimate newspapers cluck-clucked properly over Kasherman’s death, hoping that the latest killing would do what police and city officials had failed to do: put a stop to blackmail parading as journalism.”

The Minneapolis Star Journal staged this re-enactment for a front page photo illustration for its Jan. 23, 1945 edition

The moral, then: Kasherman was a petty criminal, a journalistic impostor, whose removal from the streets was a disinfectant. The greater offense, once again: crime masquerading as journalism, not a man dying because someone didn’t like what he wrote. Time’s article announced to the nation that Kasherman’s death should be a matter of celebration, not outrage.

Yet the third drive-by killing of a journalist in 11 years was the third strike for Minneapolis.

The records that survive of the Minneapolis police investigation reveal a meandering and half-hearted inquiry. Though the detectives collected Kasherman’s writings, they never sought clues within them. They talked to some mental patients who claimed responsibility, and chased some dubious leads to Chicago and New Orleans. They did get around to talking to real gangsters, people who likely knew something about why Kasherman was bumped off. Unless they were expecting a spontaneous confession, the cops were just going through the motions. No one collected Mayor Marvin Kline’s promised $500 reward. Even Kasherman’s brother, Ed Keller, described the deceased as mentally ill and predicted that no one would ever be held responsible for the homicide.

In a futile gesture, someone associated with a good government group brought a list of questions to the grand jury investigating the murder. One of them said, “Don’t you think ‘Truth’ should predominate – wouldn’t you say there was some truth in Kasherman’s paper? Did you ignore his exposure?”

There’s nothing in the police file that indicates those questions were ever answered.

But there were investigators who had motives to solve the case, beyond justice for Arthur Kasherman. The day after Kasherman’s murder, detectives combed through boxes full of papers in what the newspapers breathlessly described as Kasherman’s “secret archive,” around the corner from his apartment. One of them was William Simms, an investigator in the office of the top prosecutor, Hennepin County Attorney Mike Dillon.

For Dillon and others in Minnesota’s newly created Democratic-Farmer-Labor Party, Kasherman’s death had become a symbol of a city still ruled by gangsters, and it was seized upon by supporters of a young DFL mayoral candidate, Hubert Humphrey. Two years earlier, Simms had been planted in the prosecutor’s office by Humphrey and his supporters for the sole purpose of gathering evidence of police corruption. That evidence could help build Humphrey’s case for his second challenge against Mayor Kline, a Republican.

Simms couldn’t clear Kasherman’s case, but before the election, he found another way to use Kasherman’s relentless attacks on Kline to his patron’s benefit.

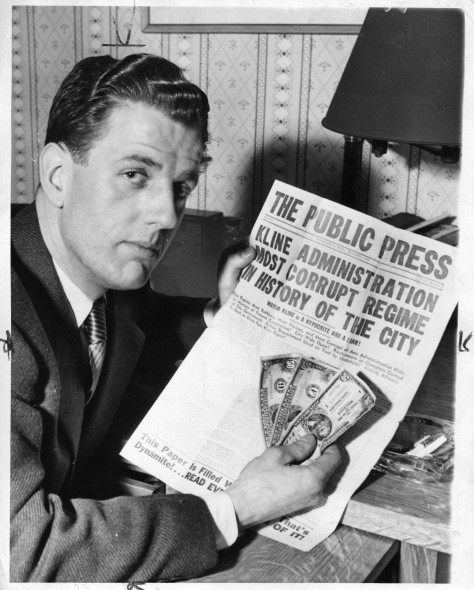

One month after Kasherman’s death, the investigation had stalled. Nevertheless, the Minneapolis Star Journal put a story on its front page headlined: “Kasherman ‘Hush Cash’ Discovered.” It’s accompanied by a curious photo: William Simms, the county attorney’s investigator, holding up a copy of the Public Press with the damning headline about Kline’s corrupt regime. The three $50 bills are supposedly “hush money,” concealed in unread newspapers, but in this context clearly stand in for the purported corruption in City Hall.

Simms recalled the circumstances in a 1978 interview: Kasherman was “killed… murdered by presumably some of the underworld characters in Minneapolis. Because of the nature of the death we sought a court permission to go into his safety deposit box, and Mike Dillon and George Totten were the two people that were authorized to open the box. And I was present, and in this box was a copy of this Free Press [sic] newspaper. In the fold of the newspaper, I’ve got a picture of it myself at home, were three $50 bills. What they were … where they came from … nobody ever knew, but … then the picture… appeared in the newspaper with … Kline administration most corrupt in the history of the city.”

During that interview, Simms was talking to Arthur Naftalin, who was Humphrey’s publicist at the time, two political operatives reminiscing about a dirty trick more than 30 years earlier. It was Naftalin who planted the story with a sympathetic reporter at the Star Journal. The story was published weeks before the election, but it fails to note that the man holding the money and the newspaper was Hubert Humphrey’s campaign manager, expertly smearing his opponent with the assistance of a willing media. The same media that felt so superior to people like Arthur Kasherman.

“They never did find out who did it,” recalled Ed Ryan, the Minneapolis police officer lauded by Kasherman in his newspapers. “It was one of those unsolved murders like Howard Guilford, Walter Liggett, Johnson the labor man and I don’t know how many others. But that was just was needed in Humphrey’s campaign because by this time people are really getting fed up. And Humphrey was really going to town on this crime and corruption.”

Humphrey, running on a “clean up the city” platform, crushed Kline in the election. Kasherman blasted Kline out of the mayor’s office after all, even if took a trip to the morgue to do it. Ryan, the man Kasherman constantly boosted in his newspapers, became the police chief.

More than 60 years later, Kasherman still haunts Minneapolis City Hall. He doesn’t have a statue, unlike the man he unintentionally helped elect. The water fountain in the hallway that he once called his “office” is long gone. But he’s there for anyone to see, in the yellowing pages of three of his newspapers, preserved as evidence in a manila file folder in the police records vault, in case anyone ever tries again to find out who rubbed him out.